Scientists Prove X-ray Laser Can Solve Protein Structures from Scratch

A study shows for the first time that X-ray lasers can be used to generate a complete 3-D model of a protein without any prior knowledge of its structure.

Menlo Park, Calif. — A study shows for the first time that X-ray lasers can be used to generate a complete 3-D model of a protein without any prior knowledge of its structure.

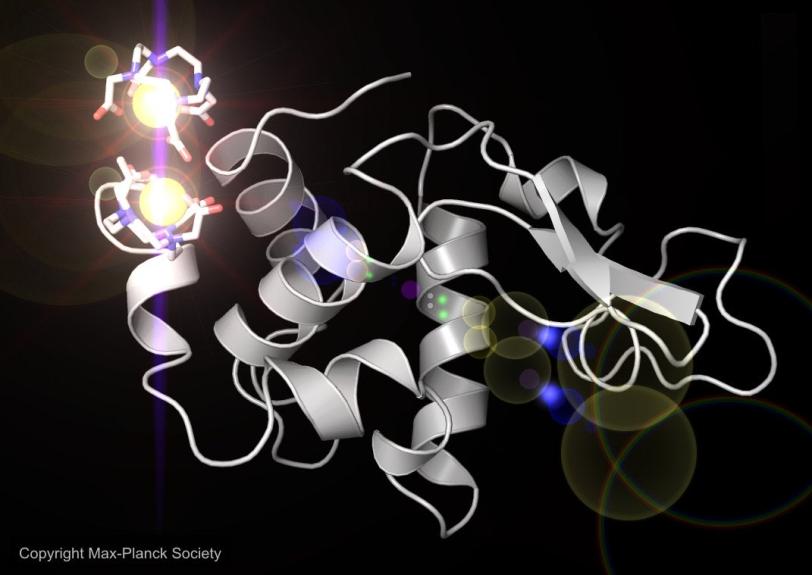

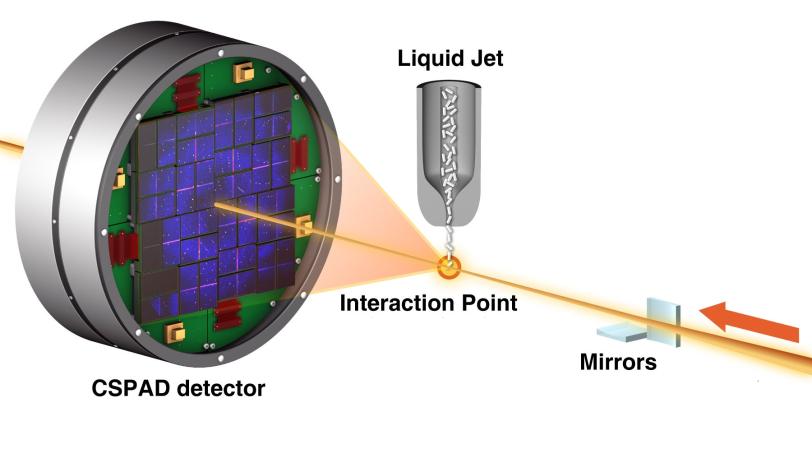

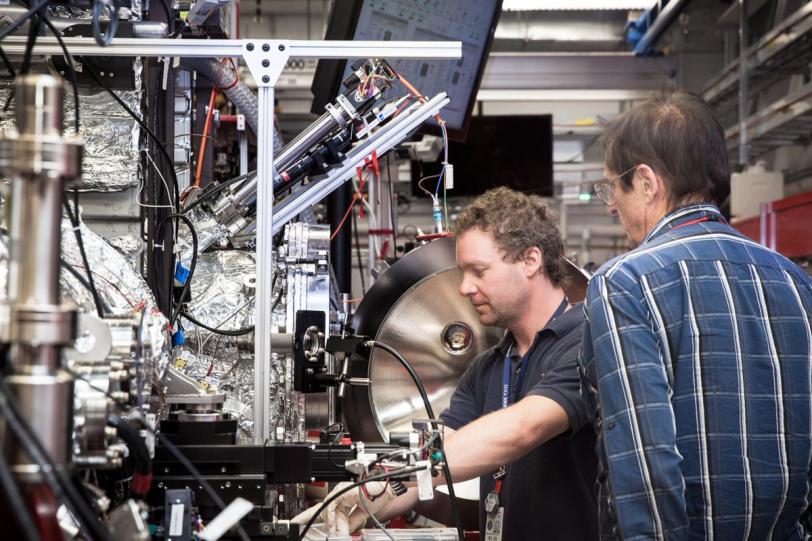

An international team of researchers working at the Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory produced from scratch an accurate model of lysozyme, a well-studied enzyme found in egg whites, using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser and sophisticated computer analysis tools.

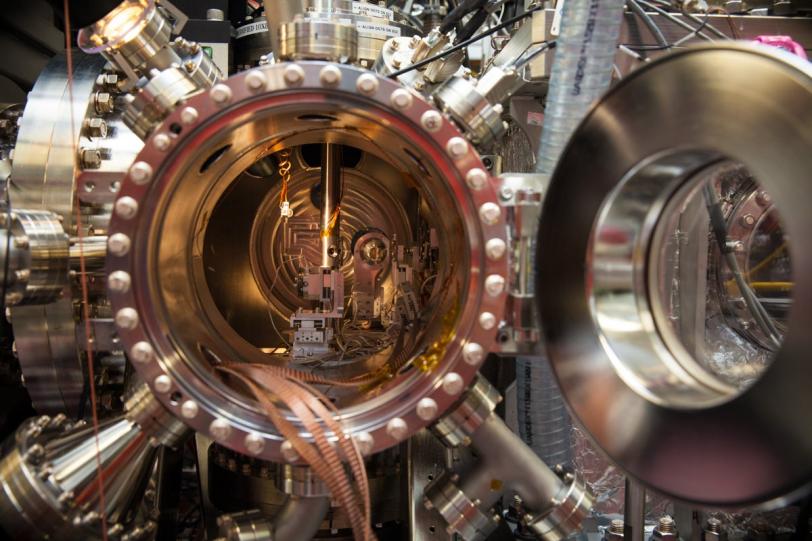

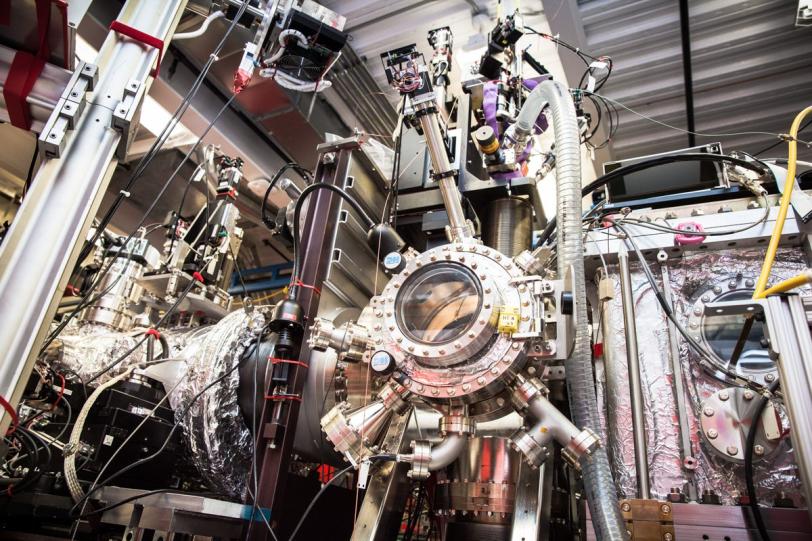

The experiment proves that X-ray lasers can play a leading role in studying important biomolecules of unknown structure. The special attributes of LCLS, which allow the study of very small crystals, could cement its role in hunting down many important biological structures that have so far remained out of reach because they form crystals too small for analysis with conventional X-ray sources.

"Determining protein structures using X-ray lasers requires averaging a gigantic amount of data to get a sufficiently accurate signal, and people wondered if this really could be done,” said Thomas Barends, a staff scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Germany who participated in the research. "Now we have experimental evidence. This really opens the door to new discoveries."

Collaborators from SLAC and Arizona State University also participated in the research, which was published Nov. 24 in Nature.

The underlying technique, called X-ray crystallography, is credited with solving the vast majority of all known protein structures and is associated with numerous Nobel Prizes since its first use just over a century ago.

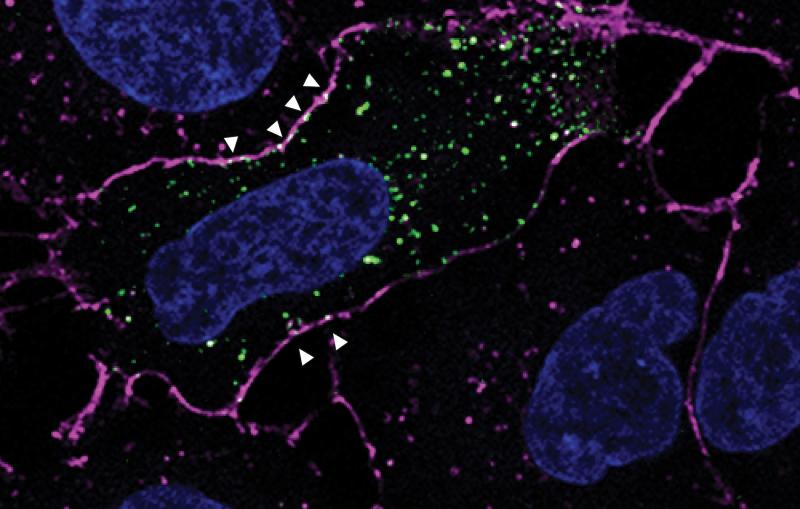

Protein structures tie directly to their functions, such as how they bind and interact with other molecules, and thus provide vital details for developing highly targeted disease-fighting drugs. But many protein structures that are considered promising targets for new medicines remain unknown, mainly because they don't form crystals that can be deciphered with existing techniques.

This work is the latest in a rapid progression of important advances at LCLS, which began operations for users in 2010. For example, last year researchers used LCLS to determine the structure of an enzyme that can hold African sleeping sickness in check, which makes it a promising drug target. However, those previous studies relied on data from similar, known structures to fill in common data gaps.

For this study the researchers chose lysozyme, whose structure has been known for decades, because it offered a good test of whether their method produced accurate results. They soaked lysozyme crystals in a solution containing gadolinium, a metal that bonded with the lysozyme to produce a strong signal when subjected to the intense X-ray light. It was this signal from the gadolinium atoms that enabled exact reconstruction of the lysozyme molecule.

The team hopes to adapt and refine the technique to explore more complex proteins such as membrane proteins, which serve a range of important cellular functions and are the target of more than half of all new drugs in development. Only a small fraction of the thousands of membrane proteins have been completely mapped.

"This study is an important milestone on which the field will build further," said John R. Helliwell, emeritus professor of chemistry at the University of Manchester and formerly a director of the Synchrotron Radiation Source at Daresbury Laboratory in England. "The X-ray laser is bringing new opportunities and new ideas for 3-D structure determination of ever-smaller samples. The use of computers to automate this process is a triumph."

Barends said the latest results are a remarkable achievement, given that it took just a few years for LCLS to reach this milestone. "Further improvements in X-ray detectors, software and crystal formation and delivery techniques should enable more discoveries in the coming years," he said.

Backstory: Marc Messerschmidt, Staff Scientist

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC's LCLS is the world's most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Citation: T. Barends et al., Nature, 24 November 2013 (10.1038/nature12773)

Press Office Contact:

Manuel Gnida, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: mgnida@slac.stanford.edu, 415-308-7832

Scientist Contacts:

Thomas Barends, Max Planck Institute for Medical Research: Thomas.Barends@mpimf-heidelberg.mpg.de

Ilme Schlichting, Max Planck Institute for Medical Research: Ilme.Schlichting@mpimf-heidelberg.mpg.de

Sebastien Boutet, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: sboutet@slac.stanford.edu